AMD Instinct™ MI Series Accelerator Performance Model

Omniperf makes available an extensive list of metrics to better understand achieved application performance on AMD Instinct™ MI accelerators including Graphics Core Next (GCN) GPUs such as the AMD Instinct MI50, CDNA™ accelerators such as the MI100, and CDNA™ 2 accelerators such as MI250X/250/210.

To best utilize this profiling data, it is vital to understand the role of various hardware blocks of AMD Instinct accelerators. This section aims to describe each hardware block on the accelerator as interacted with by a software developer, and give a deeper understanding of the metrics reported therein. Refer to Profiling with Omniperf by Example for more practical examples and detail on how to use Omniperf to optimize your code.

Note

In this document, we use MI2XX to refer to any of the AMD Instinct™ MI250X, MI250, and MI210 CDNA2 accelerators interchangeably for situations where the exact product in question is not relevant.

For more details on the differences between these accelerators, we refer the reader to the MI250X, MI250 and MI210 product pages.

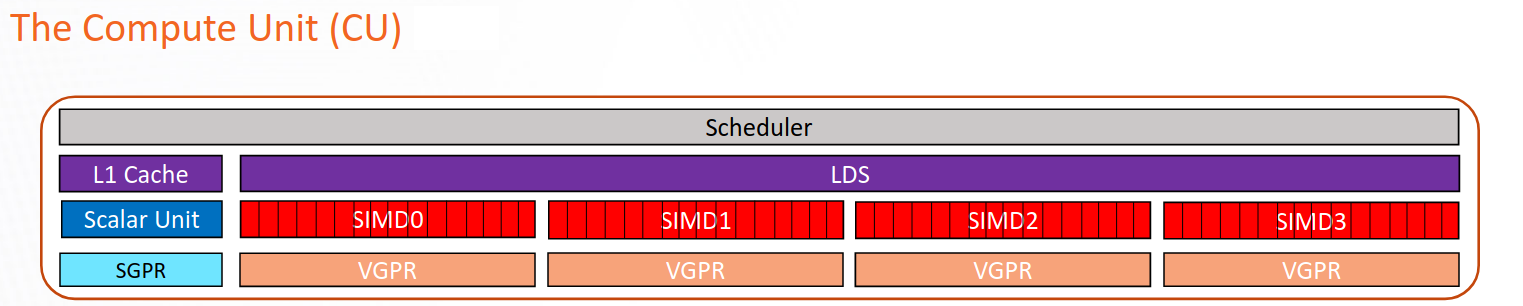

Compute Unit (CU)

The Compute Unit (CU) is responsible for executing a user’s kernels on AMD’s CDNA™ accelerators. All wavefronts of a workgroup are scheduled on the same CU.

The CU consists of several independent pipelines / functional units:

The vector arithmetic logic unit (VALU) is composed of multiple Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD) vector processors, Vector General Purpose Registers (VGPRs) and instruction buffers. The VALU is responsible for executing much of the computational work on CDNA accelerators, including (but not limited to) floating-point operations (FLOPs), integer operations (IOPs), etc.

The vector memory (VMEM) unit is responsible for issuing loads, stores and atomic operations that interact with the memory system.

The Scalar Arithmetic Logic Unit (SALU) is shared by all threads in a wavefront, and is responsible for executing instructions that are known to be uniform across the wavefront at compile-time. The SALU has a memory unit (SMEM) for interacting with memory, but it cannot issue separately from the SALU.

The Local Data Share (LDS) is an on-CU software-managed scratchpad memory that can be used to efficiently share data between all threads in a workgroup.

The scheduler is responsible for issuing and decoding instructions for all the wavefronts on the compute unit.

The vector L1 data cache (vL1D) is the first level cache local to the compute unit. On current CDNA accelerators, the vL1D is write-through. The vL1D caches from multiple compute units are kept coherent with one another through software instructions.

CDNA accelerators — i.e., the MI100 and newer — contain specialized matrix-multiplication accelerator pipelines known as the Matrix Fused Multiply-Add (MFMA).

For a more thorough description of a compute unit on a CDNA accelerator, see An introduction to AMD GPU Programming with HIP, specifically slides 22-28, and Layla Mah’s: The AMD GCN Architecture - A Crash Course, slide 27.

The Pipeline Descriptions section details the various execution pipelines (VALU, SALU, LDS, Scheduler, etc.). The metrics presented by Omniperf for these pipelines are described in Pipeline Metrics section. Finally, the vL1D cache and LDS will be described their own sections.

Pipeline Descriptions

Vector Arithmetic Logic Unit (VALU)

The vector arithmetic logic unit (VALU) executes vector instructions over an entire wavefront, each work-item (or, vector-lane) potentially operating on distinct data. The VALU of a CDNA accelerator or GCN GPU typically consists of:

four 16-wide SIMD processors (see An introduction to AMD GPU Programming with HIP for more details)

four 64 or 128 KiB VGPR files (yielding a total of 256-512 KiB total per CU), see AGPRs for more detail.

An instruction buffer (per-SIMD) that contains execution slots for up to 8 wavefronts (for 32 total wavefront slots on each CU).

A vector memory (VMEM) unit which transfers data between VGPRs and memory; each work-item supplies its own memory address and supplies or receives unique data.

CDNA accelerators, such as the MI100 and MI2XX, contain additional Matrix Fused Multiply-Add (MFMA) units.

In order to support branching / conditionals, each wavefront in the VALU has a distinct execution mask which determines which work-items in the wavefront are active for the currently executing instruction. When executing a VALU instruction, inactive work-items (according to the current execution mask of the wavefront) do not execute the instruction and are treated as no-ops.

Note

On GCN GPUs and the CDNA MI100 accelerator, there are slots for up to 10 wavefronts in the instruction buffer, but generally occupancy is limited by other factors to 32 waves per Compute Unit. On the CDNA2 MI2XX series accelerators, there are only 8 waveslots per-SIMD.

Scalar Arithmetic Logic Unit (SALU)

The scalar arithmetic logic unit (SALU) executes instructions that are shared between all work-items in a wavefront. This includes control-flow – such as if/else conditionals, branches and looping – pointer arithmetic, loading common values, etc. The SALU consists of:

a scalar processor capable of various arithmetic, conditional, and comparison (etc.) operations. See, e.g., Chapter 5. Scalar ALU Operations of the CDNA2 Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) Guide for more detail.

a 12.5 KiB Scalar General Purpose Register (SGPR) file

a scalar memory (SMEM) unit which transfers data between SGPRs and memory

Data loaded by the SMEM can be cached in the scalar L1 data cache, and is typically only used for read-only, uniform accesses such as kernel arguments, or HIP’s __constant__ memory.

Branch

The branch unit is responsible for executing jumps and branches to execute control-flow operations. Note that Branch operations are not used for execution mask updates, but only for “whole wavefront” control-flow changes.

Scheduler

The scheduler is responsible for arbitration and issue of instructions for all the wavefronts currently executing on the CU. On every clock cycle, the scheduler:

considers waves from one of the SIMD units for execution, selected in a round-robin fashion between the SIMDs in the compute unit

issues up to one instruction per wavefront on the selected SIMD

issues up to one instruction per each of the instruction categories among the waves on the selected SIMD:

This gives a maximum of five issued Instructions Per Cycle (IPC), per-SIMD, per-CU (AMD GPU HIP Training, GCN Crash Course).

On CDNA accelerators with MFMA instructions, these are issued via the VALU. Some of them will execute on a separate functional unit and typically allow other VALU operations to execute in their shadow (see the MFMA section for more detail).

Note

The IPC model used by Omniperf omits the following two complications for clarity. First, CDNA accelerators contain other execution units on the CU that are unused for compute applications. Second, so-called “internal” instructions (see Layla Mah’s GCN Crash Course, slide 29) are not issued to a functional unit, and can technically cause the maximum IPC to exceed 5 instructions per-cycle in special (largely unrealistic) cases. The latter issue is discussed in more detail in our ‘internal’ IPC example.

Matrix Fused Multiply-Add (MFMA)

CDNA accelerators, such as the MI100 and MI2XX, contain specialized hardware to accelerate matrix-matrix multiplications, also known as Matrix Fused Multiply-Add (MFMA) operations. The exact operation types and supported formats may vary by accelerator. The reader is referred to the AMD matrix cores blog post on GPUOpen for a general discussion of these hardware units. In addition, to explore the available MFMA instructions in-depth on various AMD accelerators (including the CDNA line), we recommend the AMD Matrix Instruction Calculator.

$ ./matrix_calculator.py --architecture cdna2 --instruction v_mfma_f32_4x4x1f32 --detail-instruction

Architecture: CDNA2

Instruction: V_MFMA_F32_4X4X1F32

Encoding: VOP3P-MAI

VOP3P Opcode: 0x42

VOP3P-MAI Opcode: 0x2

Matrix Dimensions:

M: 4

N: 4

K: 1

blocks: 16

Execution statistics:

FLOPs: 512

Execution cycles: 8

FLOPs/CU/cycle: 256

Can co-execute with VALU: True

VALU co-execution cycles possible: 4

Register usage:

GPRs required for A: 1

GPRs required for B: 1

GPRs required for C: 4

GPRs required for D: 4

GPR alignment requirement: 8 bytes

For the purposes of Omniperf, the MFMA unit is typically treated as a separate pipeline from the VALU, as other VALU instructions (along with other execution pipelines such as the SALU) can be issued during a portion of the total duration of an MFMA operation.

Note

The exact details of VALU and MFMA operation co-execution vary by instruction, and can be explored in more detail via the:

‘Can co-execute with VALU’

‘VALU co-execution cycles possible’

fields in the AMD Matrix Instruction Calculator’s detailed instruction information.

Non-pipeline resources

In this section, we describe a few resources that are not standalone pipelines but are important for understanding performance optimization on CDNA accelerators.

Barrier

Barriers are resources on the compute-unit of a CDNA accelerator that are used to implement synchronization primitives (e.g., HIP’s __syncthreads).

Barriers are allocated to any workgroup that consists of more than a single wavefront.

Accumulation vector General-Purpose Registers (AGPRs)

Accumulation vector General-Purpose Registers, or AGPRs, are special resources that are accessible to a subset of instructions focused on MFMA operations.

These registers allow the MFMA unit to access more than the normal maximum of 256 architected Vector General-Purpose Registers (i.e., VGPRs) by having up to 256 in the architected space and up to 256 in the accumulation space.

Traditional VALU instructions can only use VGPRs in the architected space, and data can be moved to/from VGPRs↔AGPRs using specialized instructions (v_accvgpr_*).

These data movement instructions may be used by the compiler to implement lower-cost register-spill/fills on architectures with AGPRs.

AGPRs are not available on all AMD Instinct™ accelerators. GCN GPUs, such as the AMD Instinct™ MI50 had a 256 KiB VGPR file. The AMD Instinct™ MI100 (CDNA) has a 2x256 KiB register file, where one half is available as general-purpose VGPRs, and the other half is for matrix math accumulation VGPRs (AGPRs). The AMD Instinct™ MI2XX (CDNA2) has a 512 KiB VGPR file per CU, where each wave can dynamically request up to 256 KiB of VGPRs and an additional 256 KiB of AGPRs. For more detail, the reader is referred to the following comment.

Pipeline Metrics

In this section, we describe the metrics available in Omniperf to analyze the pipelines discussed in the previous section.

Wavefront

Wavefront Launch Stats

The wavefront launch stats panel gives general information about the kernel launch:

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

Grid Size |

The total number of work-items (a.k.a “threads”) launched as a part of the kernel dispatch. In HIP, this is equivalent to the total grid size multiplied by the total workgroup (a.k.a “block”) size. |

|

Workgroup Size |

The total number of work-items (a.k.a “threads”) in each workgroup (a.k.a “block”) launched as part of the kernel dispatch. In HIP, this is equivalent to the total block size. |

|

Total Wavefronts |

The total number of wavefronts launched as part of the kernel dispatch. On AMD Instinct™ CDNA accelerators and GCN GPUs, the wavefront size is always 64 work-items. Thus, the total number of wavefronts should be equivalent to the ceiling of Grid Size divided by 64. |

|

Saved Wavefronts |

The total number of wavefronts saved at a context-save, see cwsr_enable. |

|

Restored Wavefronts |

The total number of wavefronts restored from a context-save, see cwsr_enable. |

|

VGPRs |

The number of architected vector general-purpose registers allocated for the kernel, see VALU. Note: this may not exactly match the number of VGPRs requested by the compiler due to allocation granularity. |

|

AGPRs |

The number of accumulation vector general-purpose registers allocated for the kernel, see AGPRs. Note: this may not exactly match the number of AGPRs requested by the compiler due to allocation granularity. |

|

SGPRs |

The number of scalar general-purpose registers allocated for the kernel, see SALU. Note: this may not exactly match the number of SGPRs requested by the compiler due to allocation granularity. |

|

LDS Allocation |

The number of bytes of LDS memory (a.k.a., “Shared” memory) allocated for this kernel. Note: This may also be larger than what was requested at compile-time due to both allocation granularity and dynamic per-dispatch LDS allocations. |

Bytes per workgroup |

Scratch Allocation |

The number of bytes of scratch-memory requested per work-item for this kernel. Scratch memory is used for stack memory on the accelerator, as well as for register spills/restores. |

Bytes per work-item |

Wavefront Runtime Stats

The wavefront runtime statistics gives a high-level overview of the execution of wavefronts in a kernel:

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

The total duration of the executed kernel. Note: this should not be directly compared to the wavefront cycles / timings below. |

Nanoseconds |

|

The total duration of the executed kernel in cycles. Note: this should not be directly compared to the wavefront cycles / timings below. |

Cycles |

|

Instructions per wavefront |

The average number of instructions (of all types) executed per wavefront. This is averaged over all wavefronts in a kernel dispatch. |

Instructions / wavefront |

Wave Cycles |

The number of cycles a wavefront in the kernel dispatch spent resident on a compute unit per normalization-unit. This is averaged over all wavefronts in a kernel dispatch. Note: this should not be directly compared to the kernel cycles above. |

Cycles per normalization-unit |

Dependency Wait Cycles |

The number of cycles a wavefront in the kernel dispatch stalled waiting on memory of any kind (e.g., instruction fetch, vector or scalar memory, etc.) per normalization-unit. This counter is incremented at every cycle by all wavefronts on a CU stalled at a memory operation. As such, it is most useful to get a sense of how waves were spending their time, rather than identification of a precise limiter because another wave could be actively executing while a wave is stalled. The sum of this metric, Issue Wait Cycles and Active Cycles should be equal to the total Wave Cycles metric. |

Cycles per normalization-unit |

Issue Wait Cycles |

The number of cycles a wavefront in the kernel dispatch was unable to issue an instruction for any reason (e.g., execution pipe back-pressure, arbitration loss, etc.) per normalization-unit. This counter is incremented at every cycle by all wavefronts on a CU unable to issue an instruction. As such, it is most useful to get a sense of how waves were spending their time, rather than identification of a precise limiter because another wave could be actively executing while a wave is issue stalled. The sum of this metric, Dependency Wait Cycles and Active Cycles should be equal to the total Wave Cycles metric. |

Cycles per normalization-unit |

Active Cycles |

The average number of cycles a wavefront in the kernel dispatch was actively executing instructions per normalization-unit. This measurement is made on a per-wavefront basis, and may include (e.g.,) cycles that another wavefront spent actively executing (e.g., on another execution unit) or was stalled. As such, it is most useful to get a sense of how waves were spending their time, rather than identification of a precise limiter. The sum of this metric, Issue Wait Cycles and Active Wait Cycles should be equal to the total Wave Cycles metric. |

Cycles per normalization-unit |

Wavefront Occupancy |

The time-averaged number of wavefronts resident on the accelerator over the lifetime of the kernel. Note: this metric may be inaccurate for short-running kernels (<< 1ms). |

Wavefronts |

See also

As mentioned above, the measurement of kernel cycles and time typically cannot directly be compared to e.g., Wave Cycles. This is due to two factors: first, the kernel cycles/timings are measured using a counter that is impacted by scheduling overhead, this is particularly noticeable for “short-running” kernels (typically << 1ms) where scheduling overhead forms a significant portion of the overall kernel runtime. Secondly, the Wave Cycles metric is incremented per-wavefront scheduled to a SIMD every cycle whereas the kernel cycles counter is incremented only once per-cycle when any wavefront is scheduled.

Instruction Mix

The instruction mix panel shows a breakdown of the various types of instructions executed by the user’s kernel, and which pipelines on the CU they were executed on. In addition, Omniperf reports further information about the breakdown of operation types for the VALU, vector-memory, and MFMA instructions.

Note

All metrics in this section count instructions issued, and not the total number of operations executed. The values reported by these metrics will not change regardless of the execution mask of the wavefront. We note that even if the execution mask is identically zero (i.e., no lanes are active) the instruction will still be counted, as CDNA accelerators still consider these instructions ‘issued’ see, e.g., EXECute Mask, Section 3.3 of the CDNA2 ISA Guide for more details.

Overall Instruction Mix

This panel shows the total number of each type of instruction issued to the various compute pipelines on the CU. These are:

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

VALU Instructions |

The total number of vector arithmetic logic unit (VALU) operations issued. These are the workhorses of the compute-unit, and are used to execute wide range of instruction types including floating point operations, non-uniform address calculations, transcendental operations, integer operations, shifts, conditional evaluation, etc. |

Instructions |

VMEM Instructions |

The total number of vector memory operations issued. These include most loads, stores and atomic operations and all accesses to generic, global, private and texture memory. |

Instructions |

LDS Instructions |

The total number of LDS (a.k.a., “shared memory”) operations issued. These include (e.g.,) loads, stores, atomics, and HIP’s |

Instructions |

MFMA Instructions |

The total number of matrix fused multiply-add instructions issued. |

Instructions |

SALU Instructions |

The total number of scalar arithmetic logic unit (SALU) operations issued. Typically these are used for (e.g.,) address calculations, literal constants, and other operations that are provably uniform across a wavefront. Although scalar memory (SMEM) operations are issued by the SALU, they are counted separately in this section. |

Instructions |

SMEM Instructions |

The total number of scalar memory (SMEM) operations issued. These are typically used for loading kernel arguments, base-pointers and loads from HIP’s |

Instructions |

Branch Instructions |

The total number of branch operations issued. These typically consist of jump / branch operations and are used to implement control flow. |

Instructions |

Note

Note, as mentioned in the Branch section: branch operations are not used for execution mask updates, but only for “whole wavefront” control-flow changes.

VALU Arithmetic Instruction Mix

Warning

Not all metrics in this section (e.g., the floating-point instruction breakdowns) are available on CDNA accelerators older than the MI2XX series.

This panel details the various types of vector instructions that were issued to the VALU. The metrics in this section do not include MFMA instructions using the same precision, e.g. the “F16-ADD” metric does not include any 16-bit floating point additions executed as part of an MFMA instruction using the same precision.

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

INT32 |

The total number of instructions operating on 32-bit integer operands issued to the VALU per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

INT64 |

The total number of instructions operating on 64-bit integer operands issued to the VALU per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

F16-ADD |

The total number of addition instructions operating on 16-bit floating-point operands issued to the VALU per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

F16-MUL |

The total number of multiplication instructions operating on 16-bit floating-point operands issued to the VALU per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

F16-FMA |

The total number of fused multiply-add instructions operating on 16-bit floating-point operands issued to the VALU per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

F16-TRANS |

The total number of transcendental instructions (e.g., |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

F32-ADD |

The total number of addition instructions operating on 32-bit floating-point operands issued to the VALU per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

F32-MUL |

The total number of multiplication instructions operating on 32-bit floating-point operands issued to the VALU per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

F32-FMA |

The total number of fused multiply-add instructions operating on 32-bit floating-point operands issued to the VALU per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

F32-TRANS |

The total number of transcendental instructions (e.g., |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

F64-ADD |

The total number of addition instructions operating on 64-bit floating-point operands issued to the VALU per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

F64-MUL |

The total number of multiplication instructions operating on 64-bit floating-point operands issued to the VALU per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

F64-FMA |

The total number of fused multiply-add instructions operating on 64-bit floating-point operands issued to the VALU per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

F64-TRANS |

The total number of transcendental instructions (e.g., |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

Conversion |

The total number of type conversion instructions (e.g., converting data to/from F32↔F64) issued to the VALU per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

For an example of these counters in action, the reader is referred to the VALU Arithmetic Instruction Mix example.

VMEM Instruction Mix

This section breaks down the types of vector memory (VMEM) instructions that were issued. Refer to the Instruction Counts metrics section of address-processor frontend of the vL1D cache for a description of these VMEM instructions.

MFMA Instruction Mix

Warning

The metrics in this section are only available on CDNA2 (MI2XX) accelerators and newer.

This section details the types of Matrix Fused Multiply-Add (MFMA) instructions that were issued. Note that MFMA instructions are classified by the type of input data they operate on, and not the data-type the result is accumulated to.

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

MFMA-I8 Instructions |

The total number of 8-bit integer MFMA instructions issued per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

MFMA-F16 Instructions |

The total number of 16-bit floating point MFMA instructions issued per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

MFMA-BF16 Instructions |

The total number of 16-bit brain floating point MFMA instructions issued per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

MFMA-F32 Instructions |

The total number of 32-bit floating-point MFMA instructions issued per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

MFMA-F64 Instructions |

The total number of 64-bit floating-point MFMA instructions issued per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

Compute Pipeline

FLOP counting conventions

Omniperf’s conventions for VALU FLOP counting are as follows:

Addition or Multiplication: 1 operation

Transcendentals: 1 operation

Fused Multiply-Add (FMA): 2 operations

Integer operations (IOPs) do not use this convention. They are counted as a single operation regardless of the instruction type.

Note

Packed operations which operate on multiple operands in the same instruction are counted identically to the underlying instruction type.

For example, the v_pk_add_f32 instruction on MI2XX, which performs an add operation on two pairs of aligned 32-bit floating-point operands is counted only as a single addition (i.e., 1 operation).

As discussed in the Instruction Mix section, the FLOP/IOP metrics in this section do not take into account the execution mask of the operation, and will report the same value even if the execution mask is identically zero.

For example, a FMA instruction operating on 32-bit floating-point operands (e.g., v_fma_f32 on a MI2XX accelerator) would be counted as 128 total FLOPs: 2 operations (due to the instruction type) multiplied by 64 operations (because the wavefront is composed of 64 work-items).

Compute Speed-of-Light

Warning

The theoretical maximum throughput for some metrics in this section are currently computed with the maximum achievable clock frequency, as reported by rocminfo, for an accelerator. This may not be realistic for all workloads.

This section reports the number of floating-point and integer operations executed on the VALU and MFMA units in various precisions. We note that unlike the VALU instruction mix and MFMA instruction mix sections, the metrics here are reported as FLOPs and IOPs, i.e., the total number of operations executed.

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

VALU FLOPs |

The total floating-point operations executed per second on the VALU. This is also presented as a percent of the peak theoretical FLOPs achievable on the specific accelerator. Note: this does not include any floating-point operations from MFMA instructions. |

GFLOPs |

VALU IOPs |

The total integer operations executed per second on the VALU. This is also presented as a percent of the peak theoretical IOPs achievable on the specific accelerator. Note: this does not include any integer operations from MFMA instructions. |

GIOPs |

MFMA FLOPs (BF16) |

The total number of 16-bit brain floating point MFMA operations executed per second. Note: this does not include any 16-bit brain floating point operations from VALU instructions. This is also presented as a percent of the peak theoretical BF16 MFMA operations achievable on the specific accelerator. |

GFLOPs |

MFMA FLOPs (F16) |

The total number of 16-bit floating point MFMA operations executed per second. Note: this does not include any 16-bit floating point operations from VALU instructions. This is also presented as a percent of the peak theoretical F16 MFMA operations achievable on the specific accelerator. |

GFLOPs |

MFMA FLOPs (F32) |

The total number of 32-bit floating point MFMA operations executed per second. Note: this does not include any 32-bit floating point operations from VALU instructions. This is also presented as a percent of the peak theoretical F32 MFMA operations achievable on the specific accelerator. |

GFLOPs |

MFMA FLOPs (F64) |

The total number of 64-bit floating point MFMA operations executed per second. Note: this does not include any 64-bit floating point operations from VALU instructions. This is also presented as a percent of the peak theoretical F64 MFMA operations achievable on the specific accelerator. |

GFLOPs |

MFMA IOPs (INT8) |

The total number of 8-bit integer MFMA operations executed per second. Note: this does not include any 8-bit integer operations from VALU instructions. This is also presented as a percent of the peak theoretical INT8 MFMA operations achievable on the specific accelerator. |

GIOPs |

Pipeline Statistics

This section reports a number of key performance characteristics of various execution units on the CU. The reader is referred to the Instructions per-cycle and Utilizations example for a detailed dive into these metrics, and the scheduler for a high-level overview of execution units and instruction issue.

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

IPC |

The ratio of the total number of instructions executed on the CU over the total active CU cycles. |

Instructions per-cycle |

IPC (Issued) |

The ratio of the total number of (non-internal) instructions issued over the number of cycles where the scheduler was actively working on issuing instructions. The reader is recommended the Issued IPC example for further detail. |

Instructions per-cycle |

SALU Utilization |

Indicates what percent of the kernel’s duration the SALU was busy executing instructions. Computed as the ratio of the total number of cycles spent by the scheduler issuing SALU / SMEM instructions over the total CU cycles. |

Percent |

VALU Utilization |

Indicates what percent of the kernel’s duration the VALU was busy executing instructions. Does not include VMEM operations. Computed as the ratio of the total number of cycles spent by the scheduler issuing VALU instructions over the total CU cycles. |

Percent |

VMEM Utilization |

Indicates what percent of the kernel’s duration the VMEM unit was busy executing instructions, including both global/generic and spill/scratch operations (see the VMEM instruction count metrics for more detail). Does not include VALU operations. Computed as the ratio of the total number of cycles spent by the scheduler issuing VMEM instructions over the total CU cycles. |

Percent |

Branch Utilization |

Indicates what percent of the kernel’s duration the Branch unit was busy executing instructions. Computed as the ratio of the total number of cycles spent by the scheduler issuing Branch instructions over the total CU cycles. |

Percent |

VALU Active Threads |

Indicates the average level of divergence within a wavefront over the lifetime of the kernel. The number of work-items that were active in a wavefront during execution of each VALU instruction, time-averaged over all VALU instructions run on all wavefronts in the kernel. |

Work-items |

MFMA Utilization |

Indicates what percent of the kernel’s duration the MFMA unit was busy executing instructions. Computed as the ratio of the total number of cycles spent by the MFMA was busy over the total CU cycles. |

Percent |

MFMA Instruction Cycles |

The average duration of MFMA instructions in this kernel in cycles. Computed as the ratio of the total number of cycles the MFMA unit was busy over the total number of MFMA instructions. Compare to e.g., the AMD Matrix Instruction Calculator. |

Cycles per instruction |

VMEM Latency |

The average number of round-trip cycles (i.e., from issue to data-return / acknowledgment) required for a VMEM instruction to complete. |

Cycles |

SMEM Latency |

The average number of round-trip cycles (i.e., from issue to data-return / acknowledgment) required for a SMEM instruction to complete. |

Cycles |

Note

The Branch utilization reported in this section also includes time spent in other instruction types (namely: s_endpgm) that are typically a very small percentage of the overall kernel execution. This complication is omitted for simplicity, but may result in small amounts of “branch” utilization (<<1%) for otherwise branch-less kernels.

Arithmetic Operations

This section reports the total number of floating-point and integer operations executed in various precisions. Unlike the Compute speed-of-light panel, this section reports both VALU and MFMA operations of the same precision (e.g., F32) in the same metric. Additionally, this panel lets the user control how the data is normalized (i.e., control the normalization-unit), while the speed-of-light panel does not. For more detail on how operations are counted see the FLOP counting convention section.

Warning

As discussed in the Instruction Mix section, the metrics in this section do not take into account the execution mask of the operation, and will report the same value even if EXEC is identically zero.

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

FLOPs (Total) |

The total number of floating-point operations executed on either the VALU or MFMA units, per normalization-unit |

FLOP per normalization-unit |

IOPs (Total) |

The total number of integer operations executed on either the VALU or MFMA units, per normalization-unit |

IOP per normalization-unit |

F16 OPs |

The total number of 16-bit floating-point operations executed on either the VALU or MFMA units, per normalization-unit |

FLOP per normalization-unit |

BF16 OPs |

The total number of 16-bit brain floating-point operations executed on either the VALU or MFMA units, per normalization-unit. Note: on current CDNA accelerators, the VALU has no native BF16 instructions. |

FLOP per normalization-unit |

F32 OPs |

The total number of 32-bit floating-point operations executed on either the VALU or MFMA units, per normalization-unit |

FLOP per normalization-unit |

F64 OPs |

The total number of 64-bit floating-point operations executed on either the VALU or MFMA units, per normalization-unit |

FLOP per normalization-unit |

INT8 OPs |

The total number of 8-bit integer operations executed on either the VALU or MFMA units, per normalization-unit. Note: on current CDNA accelerators, the VALU has no native INT8 instructions. |

IOPs per normalization-unit |

Local Data Share (LDS)

LDS Speed-of-Light

Warning

The theoretical maximum throughput for some metrics in this section are currently computed with the maximum achievable clock frequency, as reported by rocminfo, for an accelerator. This may not be realistic for all workloads.

The LDS speed-of-light chart shows a number of key metrics for the LDS as a comparison with the peak achievable values of those metrics. The reader is referred to our previous LDS description for a more in-depth view of the hardware.

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

Utilization |

Indicates what percent of the kernel’s duration the LDS was actively executing instructions (including, but not limited to, load, store, atomic and HIP’s |

Percent |

Access Rate |

Indicates the percentage of SIMDs in the VALU1 actively issuing LDS instructions, averaged over the lifetime of the kernel. Calculated as the ratio of the total number of cycles spent by the scheduler issuing LDS instructions over the total CU cycles. |

Percent |

Theoretical Bandwidth (% of Peak) |

Indicates the maximum amount of bytes that could have been loaded from/stored to/atomically updated in the LDS in this kernel, as a percent of the peak LDS bandwidth achievable. See the LDS Bandwidth example for more detail. |

Percent |

Bank Conflict Rate |

Indicates the percentage of active LDS cycles that were spent servicing bank conflicts. Calculated as the ratio of LDS cycles spent servicing bank conflicts over the number of LDS cycles that would have been required to move the same amount of data in an uncontended access.2 |

Percent |

Note

1 Here we assume the typical case where the workload evenly distributes LDS operations over all SIMDs in a CU (that is, waves on different SIMDs are executing similar code). For highly unbalanced workloads, where e.g., one SIMD pair in the CU does not issue LDS instructions at all, this metric is better interpreted as the percentage of SIMDs issuing LDS instructions on SIMD pairs that are actively using the LDS, averaged over the lifetime of the kernel.

2 The maximum value of the bank conflict rate is less than 100% (specifically: 96.875%), as the first cycle in the LDS scheduler is never considered contended.

Statistics

The LDS statistics panel gives a more detailed view of the hardware:

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

LDS Instructions |

The total number of LDS instructions (including, but not limited to, read/write/atomics, and e.g., HIP’s |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

Theoretical Bandwidth |

Indicates the maximum amount of bytes that could have been loaded from/stored to/atomically updated in the LDS per normalization-unit. Does not take into account the execution mask of the wavefront when the instruction was executed (see LDS Bandwidth example for more detail). |

Bytes per normalization-unit |

LDS Latency |

The average number of round-trip cycles (i.e., from issue to data-return / acknowledgment) required for an LDS instruction to complete. |

Cycles |

Bank Conflicts/Access |

The ratio of the number of cycles spent in the LDS scheduler due to bank conflicts (as determined by the conflict resolution hardware) to the base number of cycles that would be spent in the LDS scheduler in a completely uncontended case. This is the unnormalized form of the Bank Conflict Rate. |

Conflicts/Access |

Index Accesses |

The total number of cycles spent in the LDS scheduler over all operations per normalization-unit. |

Cycles per normalization-unit |

Atomic Return Cycles |

The total number of cycles spent on LDS atomics with return per normalization-unit. |

Cycles per normalization-unit |

Bank Conflicts |

The total number of cycles spent in the LDS scheduler due to bank conflicts (as determined by the conflict resolution hardware) per normalization-unit. |

Cycles per normalization-unit |

Address Conflicts |

The total number of cycles spent in the LDS scheduler due to address conflicts (as determined by the conflict resolution hardware) per normalization-unit. |

Cycles per normalization-unit |

Unaligned Stall |

The total number of cycles spent in the LDS scheduler due to stalls from non-dword aligned addresses per normalization-unit. |

Cycles per normalization-unit |

Memory Violations |

The total number of out-of-bounds accesses made to the LDS, per normalization-unit. This is unused and expected to be zero in most configurations for modern CDNA accelerators. |

Accesses per normalization-unit |

Vector L1 Cache (vL1D)

The vector L1 data (vL1D) cache is local to each compute unit on the accelerator, and handles vector memory operations issued by a wavefront. The vL1D cache consists of several components:

an address processing unit, also known as the texture addresser (TA), which receives commands (e.g., instructions) and write/atomic data from the Compute Unit, and coalesces them into fewer requests for the cache to process.

an address translation unit, also known as the L1 Unified Translation Cache (UTCL1), that translates requests from virtual to physical addresses for lookup in the cache. The translation unit has an L1 translation lookaside buffer (L1TLB) to reduce the cost of repeated translations.

a Tag RAM that looks up whether a requested cache line is already present in the cache.

the result of the Tag RAM lookup is placed in the L1 cache controller for routing to the correct location, e.g., the L2 Memory Interface for misses or the Cache RAM for hits.

the Cache RAM, also known as the texture cache (TC), stores requested data for potential reuse. Data returned from the L2 cache is placed into the Cache RAM before going down the data-return path.

a backend data processing unit, also known as the texture data (TD) that routes data back to the requesting Compute Unit.

Together, this complex is known as the vL1D, or Texture Cache per Pipe (TCP). A simplified diagram of the vL1D is presented below:

Performance model of the vL1D Cache on AMD Instinct™ MI accelerators.

vL1D Speed-of-Light

Warning

The theoretical maximum throughput for some metrics in this section are currently computed with the maximum achievable clock frequency, as reported by rocminfo, for an accelerator. This may not be realistic for all workloads.

The vL1D’s speed-of-light chart shows several key metrics for the vL1D as a comparison with the peak achievable values of those metrics.

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

Hit Rate |

The ratio of the number of vL1D cache line requests that hit1 in vL1D cache over the total number of cache line requests to the vL1D Cache RAM. |

Percent |

Bandwidth |

The number of bytes looked up in the vL1D cache as a result of VMEM instructions, as a percent of the peak theoretical bandwidth achievable on the specific accelerator. The number of bytes is calculated as the number of cache lines requested multiplied by the cache line size. This value does not consider partial requests, so e.g., if only a single value is requested in a cache line, the data movement will still be counted as a full cache line. |

Percent |

Utilization |

Indicates how busy the vL1D Cache RAM was during the kernel execution. The number of cycles where the vL1D Cache RAM is actively processing any request divided by the number of cycles where the vL1D is active2 |

Percent |

Coalescing |

Indicates how well memory instructions were coalesced by the address processing unit, ranging from uncoalesced (25%) to fully coalesced (100%). The average number of thread-requests generated per instruction divided by the ideal number of thread-requests per instruction. |

Percent |

Note

1 The vL1D cache on AMD Instinct™ MI CDNA accelerators uses a “hit-on-miss” approach to reporting cache hits. That is, if while satisfying a miss, another request comes in that would hit on the same pending cache line, the subsequent request will be counted as a ‘hit’. Therefore, it is also important to consider the Access Latency metric in the Cache access metrics section when evaluating the vL1D hit rate.

2 Omniperf considers the vL1D to be active when any part of the vL1D (excluding the address-processor and data-return units) are active, e.g., performing a translation, waiting for data, accessing the Tag or Cache RAMs, etc.

Address Processing Unit or Texture Addresser (TA)

The vL1D’s address processing unit receives vector memory instructions (commands) along with write/atomic data from a Compute Unit and is responsible for coalescing these into requests for lookup in the vL1D RAM. The address processor passes information about the commands (coalescing state, destination SIMD, etc.) to the data processing unit for use after the requested data has been retrieved.

Omniperf reports several metrics to indicate performance bottlenecks in the address processing unit, which are broken down into a few categories:

Busy / stall metrics

Instruction counts

Spill / Stack metrics

Busy / Stall metrics

When executing vector memory instructions, the compute unit must send an address (and in the case of writes/atomics, data) to the address processing unit. When the frontend cannot accept any more addresses, it must backpressure the wave-issue logic for the VMEM pipe and prevent the issue of a vector memory instruction until a previously issued memory operation has been processed.

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

Busy |

Percent of the total CU cycles the address processor was busy |

Percent |

Address Stall |

Percent of the total CU cycles the address processor was stalled from sending address requests further into the vL1D pipeline |

Percent |

Data Stall |

Percent of the total CU cycles the address processor was stalled from sending write/atomic data further into the vL1D pipeline |

Percent |

Data-Processor → Address Stall |

Percent of total CU cycles the address processor was stalled waiting to send command data to the data processor |

Percent |

Instruction counts

The address processor also counts instruction types to give the user information on what sorts of memory instructions were executed by the kernel. These are broken down into a few major categories:

Memory type |

Usage |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Global |

Global memory |

Global memory can be seen by all threads from a process. This includes the local accelerator’s DRAM, remote accelerator’s DRAM, and the host’s DRAM. |

Generic |

Dynamic address spaces |

Generic memory, a.k.a. “flat” memory, is used when the compiler cannot statically prove that a pointer is to memory in one or the other address spaces. The pointer could dynamically point into global, local, constant, or private memory. |

Private Memory |

Register spills / Stack memory |

Private memory, a.k.a. “scratch” memory, is only visible to a particular work-item in a particular workgroup. On AMD Instinct™ MI accelerators, private memory is used to implement both register spills and stack memory accesses. |

The address processor counts these instruction types as follows:

Type |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

Global/Generic |

The total number of global & generic memory instructions executed on all compute units on the accelerator, per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

Global/Generic Read |

The total number of global & generic memory read instructions executed on all compute units on the accelerator, per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

Global/Generic Write |

The total number of global & generic memory write instructions executed on all compute units on the accelerator, per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

Global/Generic Atomic |

The total number of global & generic memory atomic (with and without return) instructions executed on all compute units on the accelerator, per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

Spill/Stack |

The total number of spill/stack memory instructions executed on all compute units on the accelerator, per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

Spill/Stack Read |

The total number of spill/stack memory read instructions executed on all compute units on the accelerator, per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

Spill/Stack Write |

The total number of spill/stack memory write instructions executed on all compute units on the accelerator, per normalization-unit. |

Instruction per normalization-unit |

Spill/Stack Atomic |

The total number of spill/stack memory atomic (with and without return) instructions executed on all compute units on the accelerator, per normalization-unit. Typically unused as these memory operations are typically used to implement thread-local storage. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

Note

The above is a simplified model specifically for the HIP programming language that does not consider (e.g.,) inline assembly usage, constant memory usage or texture memory.

These categories correspond to:

Global/Generic: global and flat memory operations, that are used for Global and Generic memory access.

Spill/Stack: buffer instructions which are used on the MI50, MI100, and MI2XX accelerators for register spills / stack memory.

These concepts are described in more detail in the memory space section below, while generic memory access is explored in the generic memory benchmark section.

Spill/Stack metrics

Finally, the address processing unit contains a separate coalescing stage for spill/stack memory, and thus reports:

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

Spill/Stack Total Cycles |

The number of cycles the address processing unit spent working on spill/stack instructions, per normalization-unit. |

Cycles per normalization-unit |

Spill/Stack Coalesced Read Cycles |

The number of cycles the address processing unit spent working on coalesced spill/stack read instructions, per normalization-unit. |

Cycles per normalization-unit |

Spill/Stack Coalesced Write Cycles |

The number of cycles the address processing unit spent working on coalesced spill/stack write instructions, per normalization-unit |

Cycles per normalization-unit |

L1 Unified Translation Cache (UTCL1)

After a vector memory instruction has been processed/coalesced by the address processing unit of the vL1D, it must be translated from a virtual to physical address. This process is handled by the L1 Unified Translation Cache (UTCL1). This cache contains a L1 Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) which stores recently translated addresses to reduce the cost of subsequent re-translations.

Omniperf reports the following L1 TLB metrics:

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

Requests |

The number of translation requests made to the UTCL1 per normalization-unit. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Hits |

The number of translation requests that hit in the UTCL1, and could be reused, per normalization-unit. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Hit Ratio |

The ratio of the number of translation requests that hit in the UTCL1 divided by the total number of translation requests made to the UTCL1. |

Percent |

Translation Misses |

The total number of translation requests that missed in the UTCL1 due to translation not being present in the cache, per normalization-unit. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Permission Misses |

The total number of translation requests that missed in the UTCL1 due to a permission error, per normalization-unit. This is unused and expected to be zero in most configurations for modern CDNA accelerators. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Note

On current CDNA accelerators, such as the MI2XX, the UTCL1 does not count hit-on-miss requests.

Vector L1 Cache RAM (TC)

After coalescing in the address processing unit of the v1LD, and address translation in the L1 TLB the request proceeds to the Cache RAM stage of the pipeline. Incoming requests are looked up in the cache RAMs using parts of the physical address as a tag. Hits will be returned through the data-return path, while misses will routed out to the L2 Cache for servicing.

The metrics tracked by the vL1D RAM include:

Stall metrics

Cache access metrics

vL1D-L2 transaction detail metrics

vL1D cache stall metrics

The vL1D also reports where it is stalled in the pipeline, which may indicate performance limiters of the cache. A stall in the pipeline may result in backpressuring earlier parts of the pipeline, e.g., a stall on L2 requests may backpressure the wave-issue logic of the VMEM pipe and prevent it from issuing more vector memory instructions until the vL1D’s outstanding requests are completed.

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

Stalled on L2 Data |

The ratio of the number of cycles where the vL1D is stalled waiting for requested data to return from the L2 cache divided by the number of cycles where the vL1D is active. |

Percent |

Stalled on L2 Requests |

The ratio of the number of cycles where the vL1D is stalled waiting to issue a request for data to the L2 cache divided by the number of cycles where the vL1D is active. |

Percent |

Tag RAM Stall (Read/Write/Atomic) |

The ratio of the number of cycles where the vL1D is stalled due to Read/Write/Atomic requests with conflicting tags being looked up concurrently, divided by the number of cycles where the vL1D is active. |

Percent |

vL1D cache access metrics

The vL1D cache access metrics broadly indicate the type of requests incoming from the cache frontend, the number of requests that were serviced by the vL1D, and the number & type of outgoing requests to the L2 cache. In addition, this section includes the approximate latencies of accesses to the cache itself, along with latencies of read/write memory operations to the L2 cache.

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

Total Requests |

The total number of incoming requests from the address processing unit after coalescing. |

Requests |

Total read/write/atomic requests |

The total number of incoming read/write/atomic requests from the address processing unit after coalescing per normalization-unit. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Cache Bandwidth |

The number of bytes looked up in the vL1D cache as a result of VMEM instructions per normalization-unit. The number of bytes is calculated as the number of cache lines requested multiplied by the cache line size. This value does not consider partial requests, so e.g., if only a single value is requested in a cache line, the data movement will still be counted as a full cache line. |

Bytes per normalization-unit |

Cache Hit Rate |

The ratio of the number of vL1D cache line requests that hit in vL1D cache over the total number of cache line requests to the vL1D Cache RAM. |

Percent |

Cache Accesses |

The total number of cache line lookups in the vL1D. |

Cache lines |

Cache Hits |

The number of cache accesses minus the number of outgoing requests to the L2 cache, i.e., the number of cache line requests serviced by the vL1D Cache RAM per normalization-unit. |

Cache lines per normalization-unit |

Invalidations |

The number of times the vL1D was issued a write-back invalidate command during the kernel’s execution per normalization-unit. This may be triggered by, e.g., the |

Invalidations per normalization-unit |

L1-L2 Bandwidth |

The number of bytes transferred across the vL1D-L2 interface as a result of VMEM instructions, per normalization-unit. The number of bytes is calculated as the number of cache lines requested multiplied by the cache line size. This value does not consider partial requests, so e.g., if only a single value is requested in a cache line, the data movement will still be counted as a full cache line. |

Bytes per normalization-unit |

L1-L2 Reads |

The number of read requests for a vL1D cache line that were not satisfied by the vL1D and must be retrieved from the to the L2 Cache per normalization-unit. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

L1-L2 Writes |

The number of post-coalescing write requests that are sent through the vL1D to the L2 cache, per normalization-unit. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

L1-L2 Atomics |

The number of atomic requests that are sent through the vL1D to the L2 cache, per normalization-unit. This includes requests for atomics with, and without return. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

L1 Access Latency |

The average number of cycles that a vL1D cache line request spent in the vL1D cache pipeline. |

Cycles |

L1-L2 Read Access Latency |

The average number of cycles that the vL1D cache took to issue and receive read requests from the L2 Cache. This number also includes requests for atomics with return values. |

Cycles |

L1-L2 Write Access Latency |

The average number of cycles that the vL1D cache took to issue and receive acknowledgement of a write request to the L2 Cache. This number also includes requests for atomics without return values. |

Cycles |

Note

All cache accesses in vL1D are for a single cache line’s worth of data. The size of a cache line may vary, however on current AMD Instinct™ MI CDNA accelerators and GCN GPUs the L1 cache line size is 64B.

vL1D - L2 Transaction Detail

This section provides a more granular look at the types of requests made to the L2 cache. These are broken down by the operation type (read / write / atomic, with, or without return), and the memory type. For more detail, the reader is referred to the Memory Types section.

Vector L1 Data-Return Path or Texture Data (TD)

The data-return path of the vL1D cache, also known as the Texture Data (TD) unit, is responsible for routing data returned from the vL1D cache RAM back to a wavefront on a SIMD. As described in the vL1D cache front-end section, the data-return path is passed information about the space requirements and routing for data requests from the VALU. When data is returned from the vL1D cache RAM, it is matched to this previously stored request data, and returned to the appropriate SIMD.

Omniperf reports the following vL1D data-return path metrics:

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

Data-return Busy |

Percent of the total CU cycles the data-return unit was busy processing or waiting on data to return to the CU. |

Percent |

Cache RAM → Data-return Stall |

Percent of the total CU cycles the data-return unit was stalled on data to be returned from the vL1D Cache RAM. |

Percent |

Workgroup manager → Data-return Stall |

Percent of the total CU cycles the data-return unit was stalled by the workgroup manager due to initialization of registers as a part of launching new workgroups. |

Percent |

Coalescable Instructions |

The number of instructions submitted to the data-return unit by the address-processor that were found to be coalescable, per normalization-unit. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

Read Instructions |

The number of read instructions submitted to the data-return unit by the address-processor summed over all compute units on the accelerator, per normalization-unit. This is expected to be the sum of global/generic and spill/stack reads in the address processor. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

Write Instructions |

The number of store instructions submitted to the data-return unit by the address-processor summed over all compute units on the accelerator, per normalization-unit. This is expected to be the sum of global/generic and spill/stack stores counted by the vL1D cache-frontend. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

Atomic Instructions |

The number of atomic instructions submitted to the data-return unit by the address-processor summed over all compute units on the accelerator, per normalization-unit. This is expected to be the sum of global/generic and spill/stack atomics in the address processor. |

Instructions per normalization-unit |

L2 Cache (TCC)

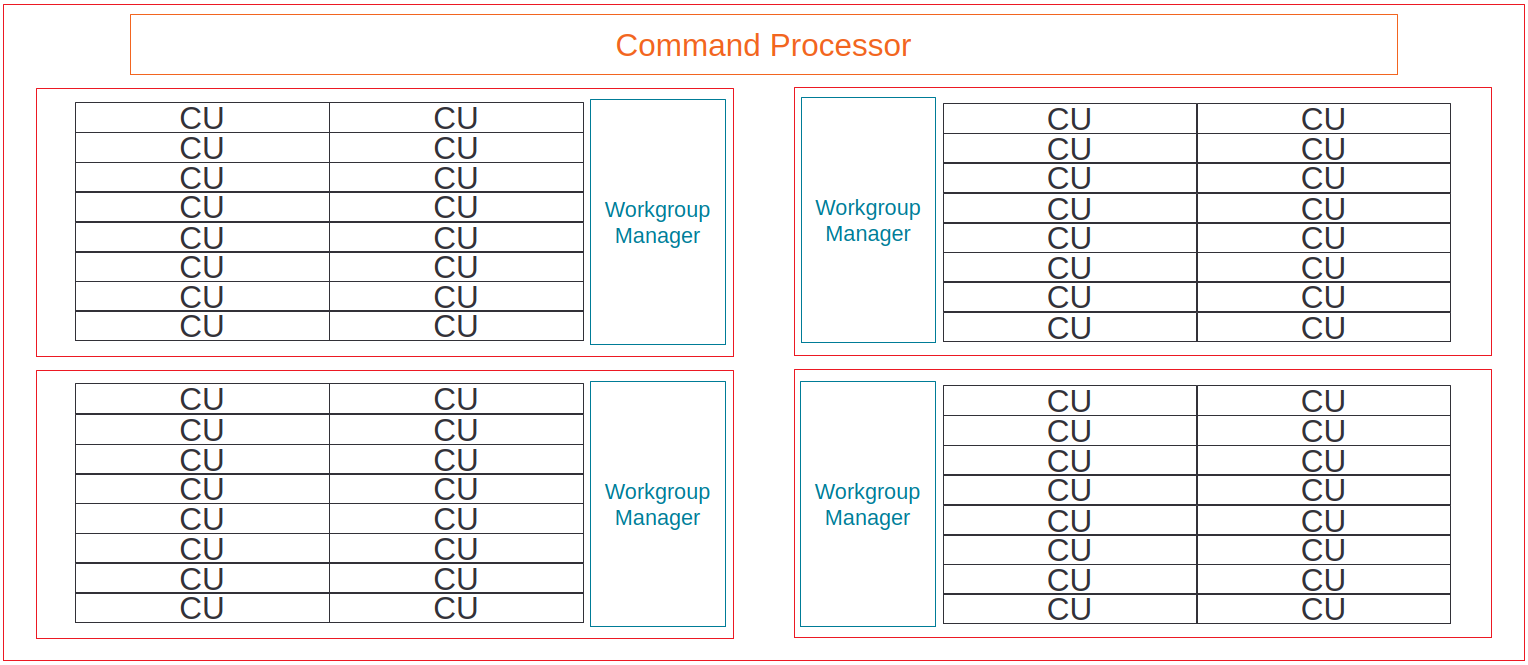

The L2 cache is the coherence point for current AMD Instinct™ MI GCN GPUs and CDNA accelerators, and is shared by all compute units on the device. Besides serving requests from the vector L1 data caches, the L2 cache also is responsible for servicing requests from the L1 instruction caches, the scalar L1 data caches and the command-processor. The L2 cache is composed of a number of distinct channels (32 on MI100/MI2XX series CDNA accelerators at 256B address interleaving) which can largely operate independently. Mapping of incoming requests to a specific L2 channel is determined by a hashing mechanism that attempts to evenly distribute requests across the L2 channels. Requests that miss in the L2 cache are passed out to Infinity Fabric™ to be routed to the appropriate memory location.

The L2 cache metrics reported by Omniperf are broken down into four categories:

L2 Speed-of-Light

L2 Cache Accesses

L2-Fabric Transactions

L2-Fabric Stalls

L2 Speed-of-Light

Warning

The theoretical maximum throughput for some metrics in this section are currently computed with the maximum achievable clock frequency, as reported by rocminfo, for an accelerator. This may not be realistic for all workloads.

The L2 cache’s speed-of-light table contains a few key metrics about the performance of the L2 cache, aggregated over all the L2 channels, as a comparison with the peak achievable values of those metrics:

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

Utilization |

The ratio of the number of cycles an L2 channel was active, summed over all L2 channels on the accelerator over the total L2 cycles. |

Percent |

Bandwidth |

The number of bytes looked up in the L2 cache, as a percent of the peak theoretical bandwidth achievable on the specific accelerator. The number of bytes is calculated as the number of cache lines requested multiplied by the cache line size. This value does not consider partial requests, so e.g., if only a single value is requested in a cache line, the data movement will still be counted as a full cache line. |

Percent |

Hit Rate |

The ratio of the number of L2 cache line requests that hit in the L2 cache over the total number of incoming cache line requests to the L2 cache. |

Percent |

L2-Fabric Read BW |

The number of bytes read by the L2 over the Infinity Fabric™ interface per unit time. |

GB/s |

L2-Fabric Write and Atomic BW |

The number of bytes sent by the L2 over the Infinity Fabric™ interface by write and atomic operations per unit time. |

GB/s |

Note

The L2 cache on AMD Instinct™ MI CDNA accelerators uses a “hit-on-miss” approach to reporting cache hits. That is, if while satisfying a miss, another request comes in that would hit on the same pending cache line, the subsequent request will be counted as a ‘hit’. Therefore, it is also important to consider the latency metric in the L2-Fabric section when evaluating the L2 hit rate.

L2 Cache Accesses

This section details the incoming requests to the L2 cache from the vL1D and other clients (e.g., the sL1D and L1I caches).

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

Bandwidth |

The number of bytes looked up in the L2 cache, per normalization-unit. The number of bytes is calculated as the number of cache lines requested multiplied by the cache line size. This value does not consider partial requests, so e.g., if only a single value is requested in a cache line, the data movement will still be counted as a full cache line. |

Bytes per normalization-unit |

Requests |

The total number of incoming requests to the L2 from all clients for all request types, per normalization-unit. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Read Requests |

The total number of read requests to the L2 from all clients. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Write Requests |

The total number of write requests to the L2 from all clients. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Atomic Requests |

The total number of atomic requests (with and without return) to the L2 from all clients. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Streaming Requests |

The total number of incoming requests to the L2 that are marked as ‘streaming’. The exact meaning of this may differ depending on the targeted accelerator, however on an MI2XX this corresponds to non-temporal load or stores. The L2 cache attempts to evict ‘streaming’ requests before normal requests when the L2 is at capacity. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Probe Requests |

The number of coherence probe requests made to the L2 cache from outside the accelerator. On an MI2XX, probe requests may be generated by e.g., writes to fine-grained device memory or by writes to coarse-grained device memory. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Hit Rate |

The ratio of the number of L2 cache line requests that hit in the L2 cache over the total number of incoming cache line requests to the L2 cache. |

Percent |

Hits |

The total number of requests to the L2 from all clients that hit in the cache. As noted in the speed-of-light section, this includes hit-on-miss requests. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Misses |

The total number of requests to the L2 from all clients that miss in the cache. As noted in the speed-of-light section, these do not include hit-on-miss requests. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Writebacks |

The total number of L2 cache lines written back to memory for any reason. Write-backs may occur due to e.g., user-code (e.g., HIP kernel calls to |

Cache lines per normalization-unit |

Writebacks (Internal) |

The total number of L2 cache lines written back to memory for internal hardware reasons, per normalization-unit. |

Cache lines per normalization-unit |

Writebacks (vL1D Req) |

The total number of L2 cache lines written back to memory due to requests initiated by the vL1D cache, per normalization-unit. |

Cache lines per normalization-unit |

Evictions (Normal) |

The total number of L2 cache lines evicted from the cache due to capacity limits, per normalization-unit, per normalization-unit. |

Cache lines per normalization-unit |

Evictions (vL1D Req) |

The total number of L2 cache lines evicted from the cache due to invalidation requests initiated by the vL1D cache, per normalization-unit. |

Cache lines per normalization-unit |

Non-hardware-Coherent Requests |

The total number of requests to the L2 to Not-hardware-Coherent (NC) memory allocations, per normalization-unit. See the Memory Types section for more detail. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Uncached Requests |

The total number of requests to the L2 that to uncached (UC) memory allocations. See the Memory Types section for more detail. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Coherently Cached Requests |

The total number of requests to the L2 that to coherently cachable (CC) memory allocations. See the Memory Types section for more detail. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Read/Write Coherent Requests |

The total number of requests to the L2 that to Read-Write coherent memory (RW) allocations. See the Memory Types section for more detail. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Note

All requests to the L2 are for a single cache line’s worth of data. The size of a cache line may vary depending on the accelerator, however on an AMD Instinct™ CDNA2 MI2XX accelerator, it is 128B, while on an MI100, it is 64B.

L2-Fabric transactions

Requests/data that miss in the L2 must be routed to memory in order to service them. The backing memory for a request may be local to this accelerator (i.e., in the local high-bandwidth memory), in a remote accelerator’s memory, or even in the CPU’s memory. Infinity Fabric™ is responsible for routing these memory requests/data to the correct location and returning any fetched data to the L2 cache. The following section describes the flow of these requests through Infinity Fabric™ in more detail, as described by Omniperf metrics, while later sections give detailed definitions of individual metrics.

Request flow

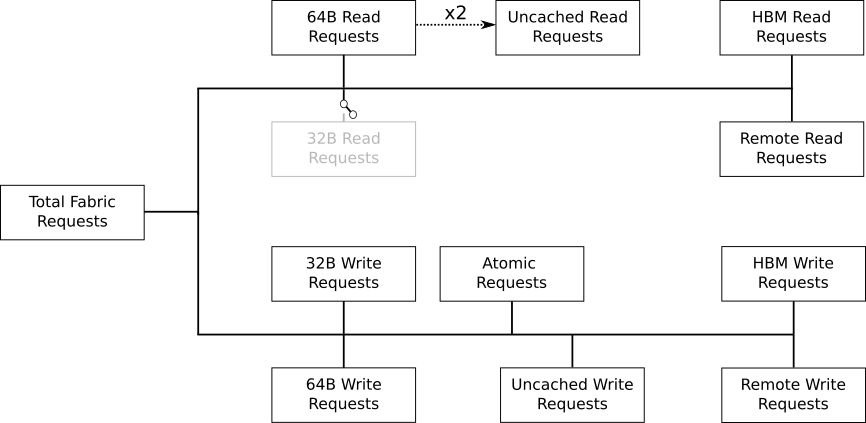

Below is a diagram that illustrates how L2↔Fabric requests are reported by Omniperf:

L2↔Fabric transaction flow on AMD Instinct™ MI accelerators.

Requests from the L2 Cache are broken down into two major categories, read requests and write requests (at this granularity, atomic requests are treated as writes).

From there, these requests can additionally subdivided in a number of ways. First, these requests may be sent across Infinity Fabric™ as different transaction sizes, 32B or 64B on current CDNA accelerators.

Note

On current CDNA accelerators, the 32B read request path is expected to be unused (hence: is disconnected in the flow diagram).

In addition, the read and write requests can be further categorized as:

uncached read/write requests, e.g., for accesses to fine-grained memory

atomic requests, e.g., for atomic updates to fine-grained memory

HBM read/write requests OR remote read/write requests, i.e., for requests to the accelerator’s local HBM OR requests to a remote accelerator’s HBM / the CPU’s DRAM.

These classifications are not necessarily exclusive, for example, a write request can be classified as an atomic request to the accelerator’s local HBM, and an uncached write request. The request-flow diagram marks exclusive classifications as a splitting of the flow, while non-exclusive requests do not split the flow line. For example, a request is either a 32B Write Request OR a 64B Write request, as the flow splits at this point:

Splitting request flow

However, continuing along, the same request might be an Atomic request and an Uncached Write request, as reflected by a non-split flow:

Non-splitting request flow

Finally, we note that uncached read requests (e.g., to fine-grained memory) are handled specially on CDNA accelerators, as indicated in the request flow diagram. These are expected to be counted as a 64B Read Request, and if they are requests to uncached memory (denoted by the dashed line), they will also be counted as two uncached read requests (i.e., the request is split):

Uncached read-request splitting.

Metrics

The following metrics are reported for the L2-Fabric interface:

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

L2-Fabric Read Bandwidth |

The total number of bytes read by the L2 cache from Infinity Fabric™ per normalization-unit. |

Bytes per normalization-unit |

HBM Read Traffic |

The percent of read requests generated by the L2 cache that are routed to the accelerator’s local high-bandwidth memory (HBM). This breakdown does not consider the size of the request (i.e., 32B and 64B requests are both counted as a single request), so this metric only approximates the percent of the L2-Fabric Read bandwidth directed to the local HBM. |

Percent |

Remote Read Traffic |

The percent of read requests generated by the L2 cache that are routed to any memory location other than the accelerator’s local high-bandwidth memory (HBM) — e.g., the CPU’s DRAM, a remote accelerator’s HBM, etc. This breakdown does not consider the size of the request (i.e., 32B and 64B requests are both counted as a single request), so this metric only approximates the percent of the L2-Fabric Read bandwidth directed to a remote location. |

Percent |

Uncached Read Traffic |

The percent of read requests generated by the L2 cache that are reading from an uncached memory allocation. Note, as described in the request-flow section, a single 64B read request is typically counted as two uncached read requests, hence it is possible for the Uncached Read Traffic to reach up to 200% of the total number of read requests. This breakdown does not consider the size of the request (i.e., 32B and 64B requests are both counted as a single request), so this metric only approximates the percent of the L2-Fabric read bandwidth directed to an uncached memory location. |

Percent |

L2-Fabric Write and Atomic Bandwidth |

The total number of bytes written by the L2 over Infinity Fabric™ by write and atomic operations per normalization-unit. Note that on current CDNA accelerators, such as the MI2XX, requests are only considered ‘atomic’ by Infinity Fabric™ if they are targeted at non-write-cachable memory, e.g., fine-grained memory allocations or uncached memory allocations on the MI2XX. |

Bytes per normalization-unit |

HBM Write and Atomic Traffic |

The percent of write and atomic requests generated by the L2 cache that are routed to the accelerator’s local high-bandwidth memory (HBM). This breakdown does not consider the size of the request (i.e., 32B and 64B requests are both counted as a single request), so this metric only approximates the percent of the L2-Fabric Write and Atomic bandwidth directed to the local HBM. Note that on current CDNA accelerators, such as the MI2XX, requests are only considered ‘atomic’ by Infinity Fabric™ if they are targeted at fine-grained memory allocations or uncached memory allocations. |

Percent |

Remote Write and Atomic Traffic |

The percent of write and atomic requests generated by the L2 cache that are routed to any memory location other than the accelerator’s local high-bandwidth memory (HBM) — e.g., the CPU’s DRAM, a remote accelerator’s HBM, etc. This breakdown does not consider the size of the request (i.e., 32B and 64B requests are both counted as a single request), so this metric only approximates the percent of the L2-Fabric Write and Atomic bandwidth directed to a remote location. Note that on current CDNA accelerators, such as the MI2XX, requests are only considered ‘atomic’ by Infinity Fabric™ if they are targeted at non-write-cachable memory, e.g., fine-grained memory allocations or uncached memory allocations on the MI2XX. |

Percent |

Atomic Traffic |

The percent of write requests generated by the L2 cache that are atomic requests to any memory location. This breakdown does not consider the size of the request (i.e., 32B and 64B requests are both counted as a single request), so this metric only approximates the percent of the L2-Fabric Write and Atomic bandwidth that is due to use of atomics. Note that on current CDNA accelerators, such as the MI2XX, requests are only considered ‘atomic’ by Infinity Fabric™ if they are targeted at fine-grained memory allocations or uncached memory allocations. |

Percent |

Uncached Write and Atomic Traffic |

The percent of write and atomic requests generated by the L2 cache that are targeting uncached memory allocations. This breakdown does not consider the size of the request (i.e., 32B and 64B requests are both counted as a single request), so this metric only approximates the percent of the L2-Fabric read bandwidth directed to uncached memory allocations. |

Percent |

Read Latency |

The time-averaged number of cycles read requests spent in Infinity Fabric™ before data was returned to the L2. |

Cycles |

Write Latency |

The time-averaged number of cycles write requests spent in Infinity Fabric™ before a completion acknowledgement was returned to the L2. |

Cycles |

Atomic Latency |

The time-averaged number of cycles atomic requests spent in Infinity Fabric™ before a completion acknowledgement (atomic without return value) or data (atomic with return value) was returned to the L2. |

Cycles |

Read Stall |

The ratio of the total number of cycles the L2-Fabric interface was stalled on a read request to any destination (local HBM, remote PCIe® connected accelerator / CPU, or remote Infinity Fabric™ connected accelerator1 / CPU) over the total active L2 cycles. |

Percent |

Write Stall |

The ratio of the total number of cycles the L2-Fabric interface was stalled on a write or atomic request to any destination (local HBM, remote accelerator / CPU, PCIe® connected accelerator / CPU, or remote Infinity Fabric™ connected accelerator1 / CPU) over the total active L2 cycles. |

Percent |

Detailed Transaction Metrics

The following metrics are available in the detailed L2-Fabric transaction breakdown table:

Metric |

Description |

Unit |

|---|---|---|

32B Read Requests |

The total number of L2 requests to Infinity Fabric™ to read 32B of data from any memory location, per normalization-unit. See request-flow for more detail. Typically unused on CDNA accelerators. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Uncached Read Requests |

The total number of L2 requests to Infinity Fabric™ to read uncached data from any memory location, per normalization-unit. 64B requests for uncached data are counted as two 32B uncached data requests. See request-flow for more detail. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

64B Read Requests |

The total number of L2 requests to Infinity Fabric™ to read 64B of data from any memory location, per normalization-unit. See request-flow for more detail. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

HBM Read Requests |

The total number of L2 requests to Infinity Fabric™ to read 32B or 64B of data from the accelerator’s local HBM, per normalization-unit. See request-flow for more detail. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Remote Read Requests |

The total number of L2 requests to Infinity Fabric™ to read 32B or 64B of data from any source other than the accelerator’s local HBM, per normalization-unit. See request-flow for more detail. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

32B Write and Atomic Requests |

The total number of L2 requests to Infinity Fabric™ to write or atomically update 32B of data to any memory location, per normalization-unit. See request-flow for more detail. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

Uncached Write and Atomic Requests |

The total number of L2 requests to Infinity Fabric™ to write or atomically update 32B or 64B of uncached data, per normalization-unit. See request-flow for more detail. |

Requests per normalization-unit |

64B Write and Atomic Requests |

The total number of L2 requests to Infinity Fabric™ to write or atomically update 64B of data in any memory location, per normalization-unit. See request-flow for more detail. |

Requests per normalization-unit |